10401 East Jefferson Avenue

Hannan Memorial YMCA, Detroit Job Corps Training Center, Women’s Justice Center

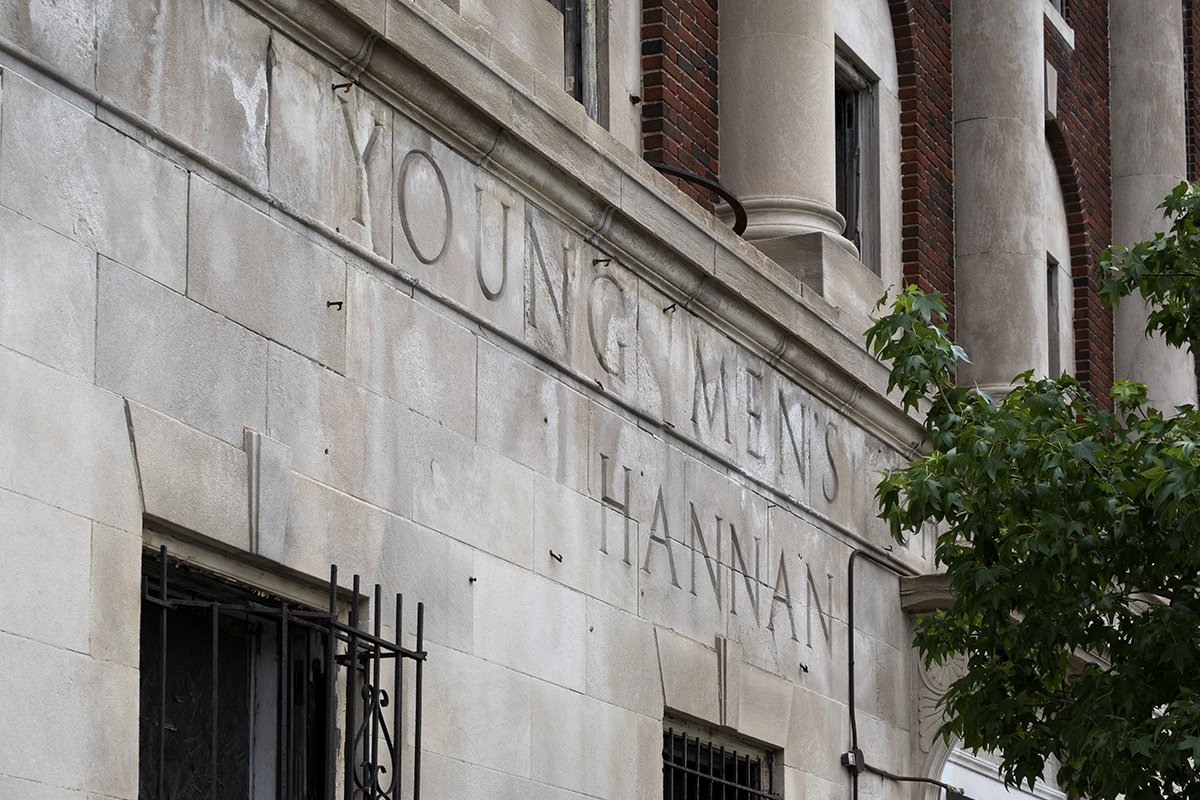

If you’ve spent time in Detroit, you’ve probably passed this building. It stands menacingly on East Jefferson Avenue across from the Detroit Water Works as it has for nearly a century. However, if Mayor Duggan gets his way, it’ll be a vacant lot soon. Before diving into this structure’s history, we must understand who its namesake was and how his name got onto a building of such stature.

William Washington Hannan was born in New York State and moved to Michigan at a young age, eventually attending the University of Michigan and relocating to Detroit after graduation to practice law. His time in the courtroom was short-lived, as he soon became involved in real estate, which was becoming a hot commodity in Detroit. He would plat numerous subdivisions around the Detroit area and hold an extensive portfolio of apartment and apartment/hotel buildings, including the Madison-Lenox, which was illegally demolished by the Ilitch family in 2005, over 100 years after Hannan funded its construction.

Hannan was the first president of the National Association of Real Estate Exchanges, which still exists today, and had amassed an estate worth at least $4,000,000 when he died on December 24, 1917. In 2023, that’s nearly $90 million. Upon his death, a significant portion of his wealth was set aside for charities. A large hall was planned in his honor downtown; however, his wife Luella decided that the money was better spent elsewhere in Detroit. She had to take the matter to court, and the judge ruled in her favor. Hannan’s funeral was at St. Paul’s Cathedral on Woodward, a church that would later receive money for new windows from the Hannah family estate.

On May 17, 1917, ground was broken for a new YMCA on East Jefferson. The branch would be named the Hannan Memorial YMCA thanks to a sizable donation from Luella. Initial reports said she had donated $500,000 of the $700,000 needed to build the structure; however, later articles cite that she fronted the entire $750,000 bill.

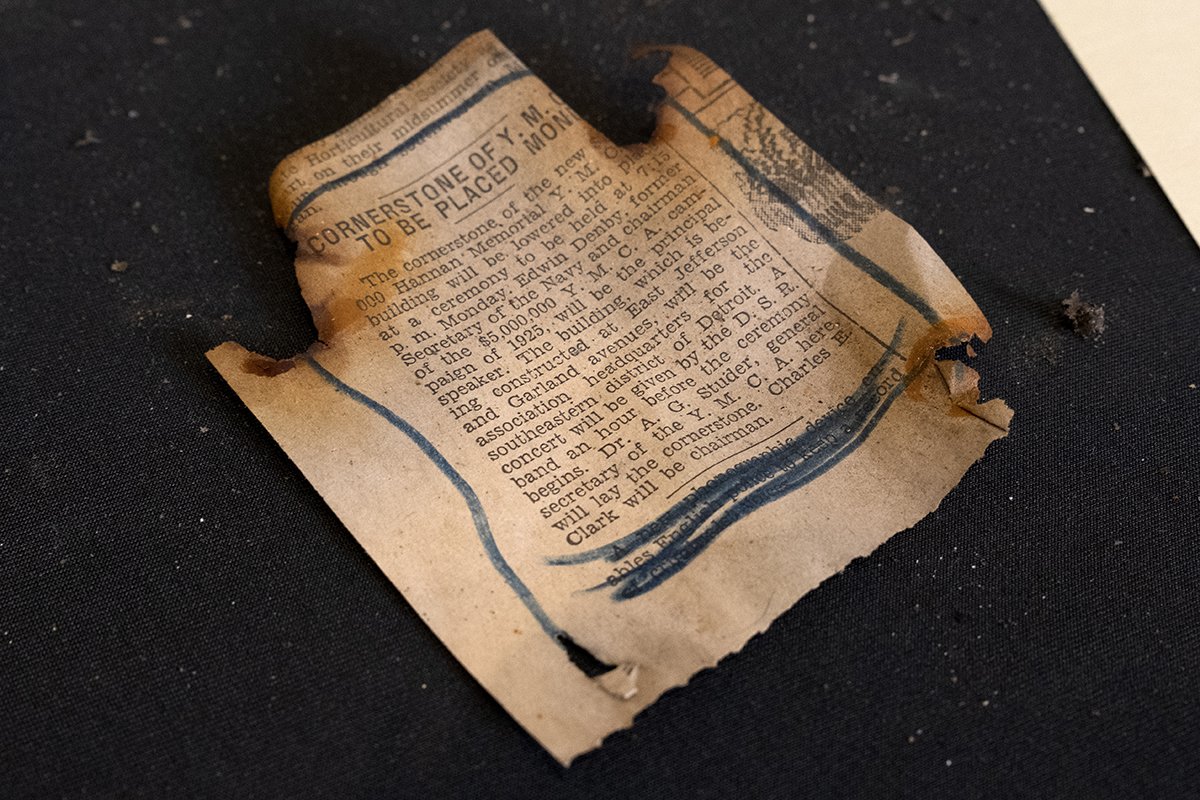

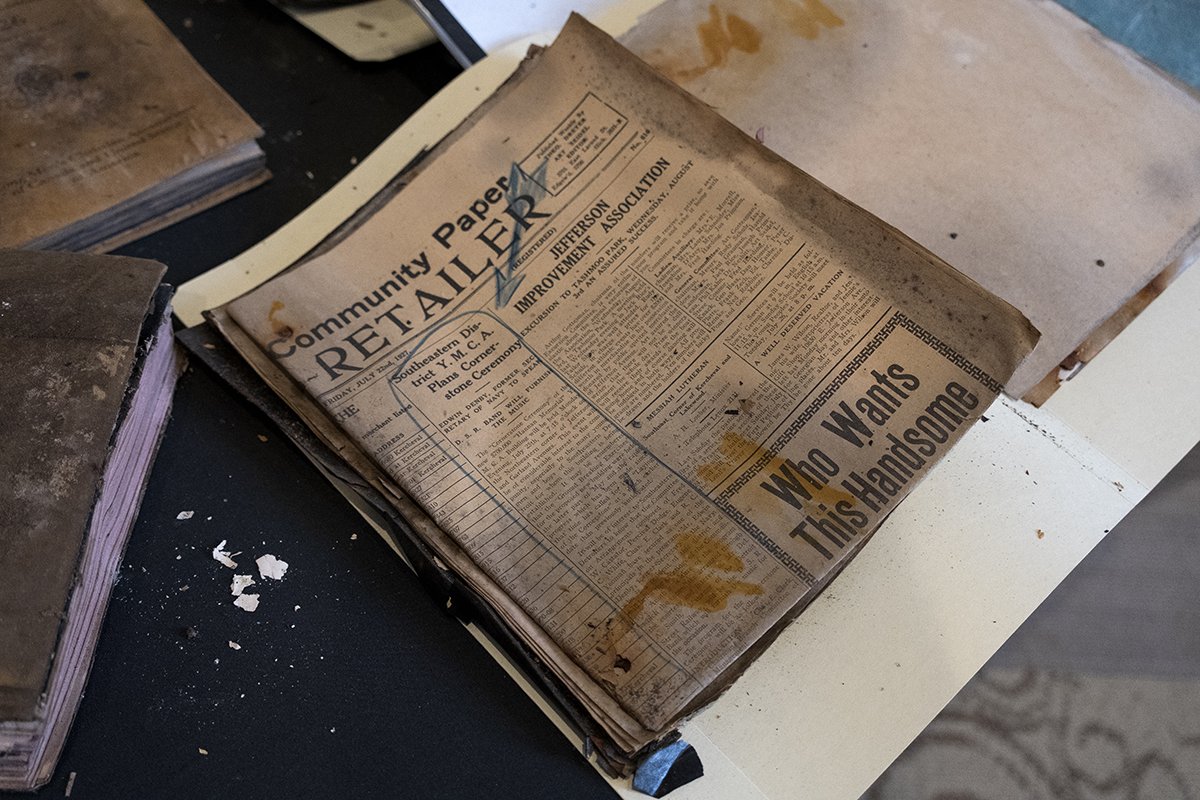

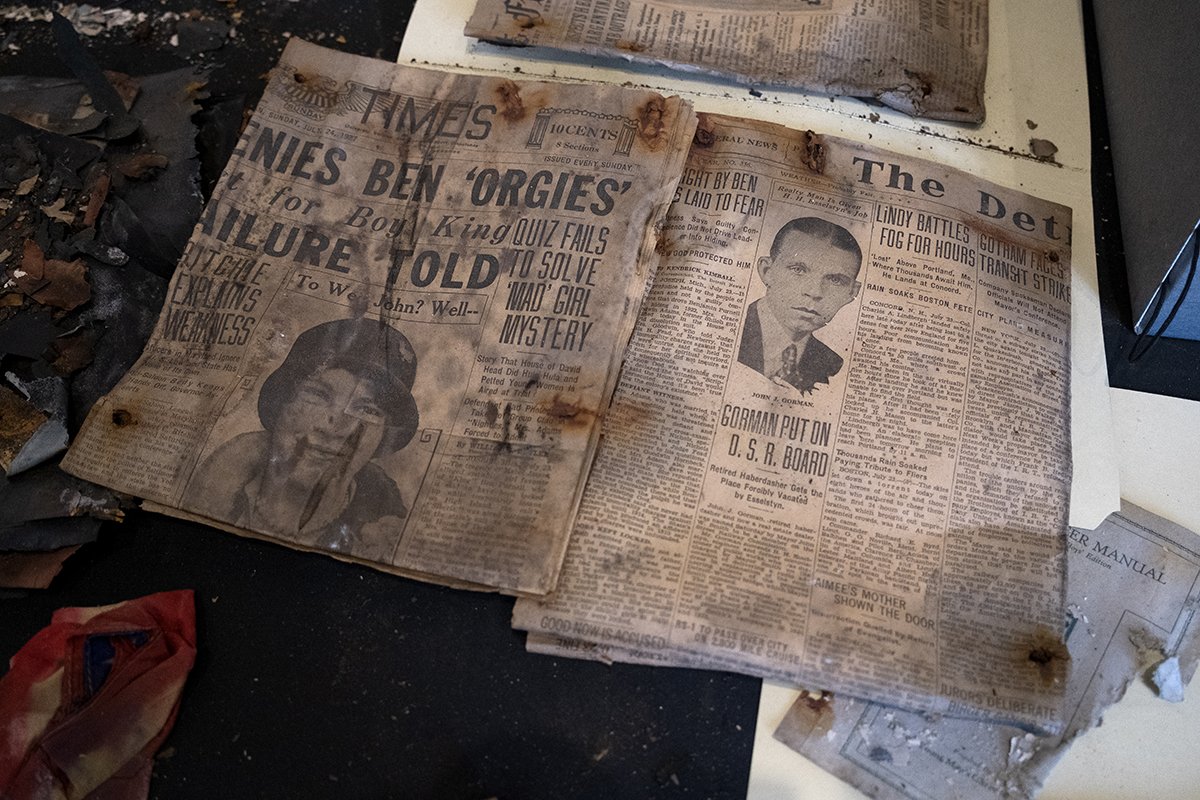

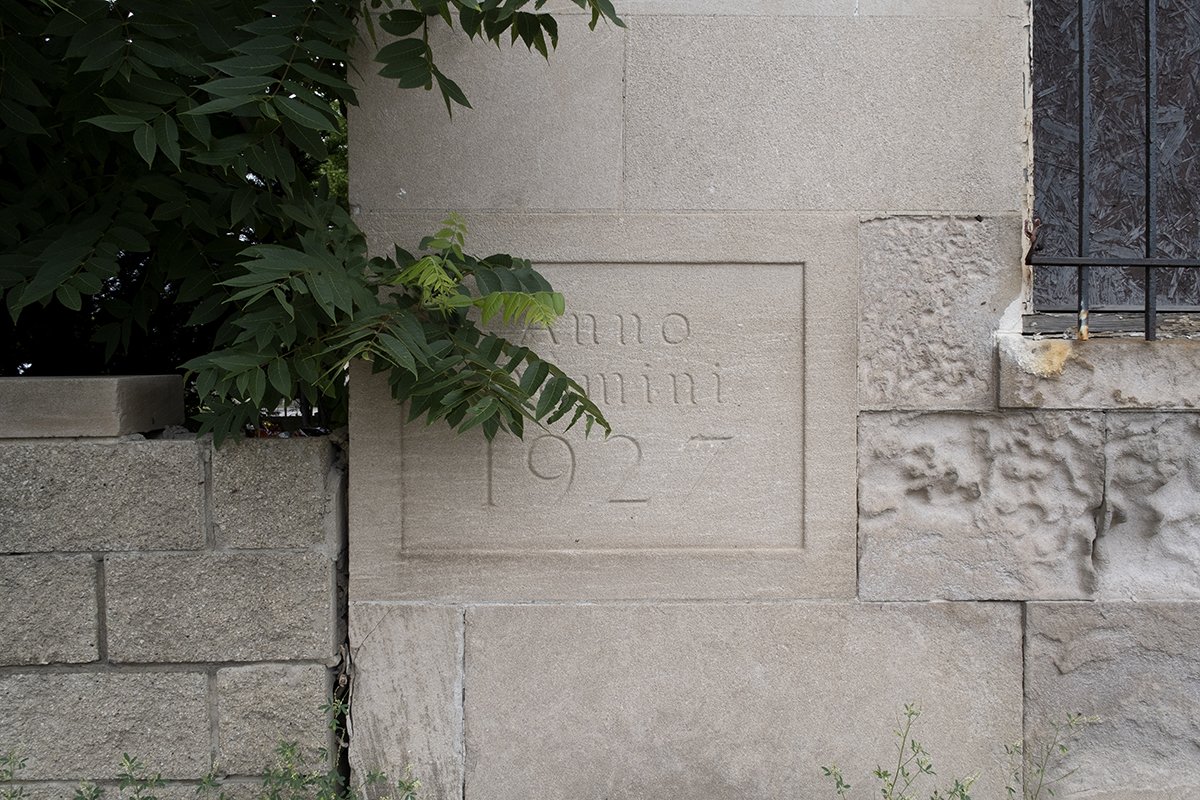

On July 25, 1927, the cornerstone was laid. It contained a time capsule that included a bible, an American flag, the oral history of the Detroit YMCA, and other signatures and paperwork. Initially set to open in April 1928, it would be pushed back a month.

On May 20, 1928, at 2:15 PM, the Hannan Memorial YMCA opened its doors. At 3 PM, a dedicatory program was held. When it opened, the neighborhoods it served had a population of nearly 200,000 people. Considering its massive presence, it felt big enough for an entire city.

Robert O. Derrick designed the structure. Although most known for designing the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Derrick did work on several smaller facilities in Detroit, including bank buildings like 7508 West Warren I’ve covered previously. The Hannah Memorial YMCA was designed with Georgian Period influences and has a court in the center, which enables more natural light inside.

It had two gymnasiums, a natatorium (indoor swimming pool), two handball courts, exercise rooms, shower facilities, social rooms, and accommodations for 178 roomers. When built, YMCAs were a common place for travelers and those figuring things out. This trend continued for decades and faded in the 1970s and 1980s.

The Hannan YMCA was an integral part of the fabric of Detroit’s east side. It provided classes, meeting spaces, sports leagues, after-school programs, an in-house newspaper, and a place for the community to unite. As Detroit changed, so did the YMCA and its patrons. However, it would close by the early 1970s.

Job Corps was a brainchild of the Kennedy administration, although it wouldn’t be implemented until after his death by Johnson’s White House. The general idea was to train kids between 16 and 24 to be employable and get their high school diplomas if they wanted to. It was a part of the Great Society program and was implemented in 1964.

Initially, Detroit did not have a Job Corps Center. In 1970, the first Detroit Job Corps Training Center opened at Fort Wayne in Southwest Detroit. Initially planned to be housed at the Maybury Sanitarium, a former tuberculosis hospital at the present location of Maybury State Park in Northville, it was decided the building in question would cost too much to heat in the winter. The Bendix Corporation ran the center at Fort Wayne, but it wouldn’t stay there long.

In 1974, the YMCA sold the building to the United States Department of Labor. They planned to use it as a Job Corps training center.

At the center, teachers and volunteers taught students welding, auto mechanics, building maintenance skills, nurses’ aid competency, and general office and business skills. Throughout the 1970s, Detroit’s Job Corps statistics weren’t great, and retention was below the national average. In 1980, alum groups were set up in ten cities to assist the Job Corps Training Centers. By that time, the operation was run by the Singer Corporation. The Metro Detroit area had an estimated 1,500 alumni at that time.

In the 1980s, statistics improved. The dropout rate fell to 19% from a staggering 30%. The program was 98% black, and the staff at the center was 80% black, which was much higher than most other centers. Other Job Corps had issues with majority black student populations being taught by a majority white staff, but that was no longer an issue in Detroit.

In this era, the Hannan Memorial YMCA Building was like a fortress. Bars were put on the windows, the building was locked, and there was security to ensure no foul play was allowed to enter the campus. There was a curfew, and drugs and fighting were a one-way ticket out of the program. According to reports, there weren’t a lot of problems at the center. For many students, this was their last shot at formal education, as the population was primarily high-school dropouts.

The 1984 class had 460 students, and 81 chose to take courses and get their high school diplomas. That might seem low, but students were not required to get their GED. The primary purpose of Job Corps was to prepare young people to work in their communities, not get them a diploma. One administrator saw it as a win because they had graduated one in five students that Detroit Public Schools had given up on entirely.

In August 1985, a fire destroyed the fourth floor of the Hannan Memorial YMCA Building. Students were living on that floor, but it didn’t appear that anyone was hurt. However, 25 students never came back after the fire. It was rebuilt.

In 1990, the Detroit Job Corps Center was eying a move to northwest Detroit at the Burtha M. Fisher Home, which had closed the year before. The space would have room for all their students to live on campus. At the old YMCA, they only had room for half. Plus, the building on Jefferson was showing signs of age, and most of the annual budget went to paying staff, not facility upgrades. The move seemed like a no-brainer; however, there was community pushback. Neighborhood groups and block clubs in northwest Detroit fought the move because they felt that the kind of kids that would attend the school were the wrong crowd and not what they wanted in their neighborhood.

The move never happened. The Burtha M. Fisher Home was demolished a few years later and is now home to a small grocery store, Citi Trends, Subway, and a few other small stores.

The Detroit Job Corps Training Center continued to look for other options, eventually finding an old hospital campus at 11801 Woodrow Wilson. At the time, it was owned by Metro Medical Group, a division of Health Alliance Plan.

I’m not certain when the Job Corps officially left 10401 East Jefferson Avenue; however, the last mention I’ve found of it in use was from May 2001. In the mid-1990s, the Vinnell Corporation took over managing the center, adding modern courses working with computers as technology advanced.

Today, Detroit’s Job Corps Training Center is still at that location and helps Detroiters to find their careers and enables them to get their GED. After the school left East Jefferson Avenue, the Hannan Memorial YMCA Building fell into turmoil—but that’s only half the story.

In 2005, the federal government gave the YMCA property to a small non-profit called the Women’s Justice Center. This wasn’t all that uncommon in that era—if you had a non-profit in Detroit and were doing some good for the world, there was land and buildings to be had. Those with the land could eliminate the liability and tax burden, and non-profits often landed with buildings too large to maintain. Often, they had good intentions, but their plans might not have been feasible, at least for the long term. However, there were some success stories. This is not one of them.

As a part of the plan for the Women’s Justice Center to get the structure for free, they had to stabilize, renovate, and utilize the property. Unfortunately, none of that happened, at least on a large scale.

In 2020, the City of Detroit sued the non-profit and got a court order to force the Women’s Justice Center to clean up and stabilize the old YMCA. Still, nothing has happened at 10401 East Jefferson Avenue. Windows and doors remain smashed open, trees and weeds grow where they shouldn’t, and the roof continues to dematerialize.

According to a recent Crains Detroit article, the city hopes to retain ownership of the property, demolish it, and hand over $20,000 to the non-profit for the land. Whereas they’ve been critical of the Women’s Justice Center for allowing the structure to fall so deep into disrepair, city officials have also thrown blame at the feds. Such a small non-profit should never have been given such a massive project without a proper plan in place for its future.

The city said it would cost nearly a million dollars to demolish the structure and 20 times that to renovate it. They hope to demolish it and sell the land to be developed by the private sector.

This one is tough for me. I understand what lousy shape the structure is in—a few years back; I found myself exploring it numerous times. The higher you went, the scarier the bones got. It’s in rough shape, and it would cost an arm and a leg and require a special person to invest in such a property.

That said, this is an integral piece of Detroit’s past. It’s a tie to Detroit’s first boom, an era of the Motor City’s history before most Detroiters could imagine what a car was, let alone owning one. Hundreds of thousands of Detroiters walked through those doors to attend meetings and events, play sports, and learn new skills. Imagine who might have stayed there on their first nights in Detroit after a long train ride to the city. Plus, they certainly don’t build structures like that anymore, and I doubt they ever will again.

I fully expect this one to have a date with the wrecking ball, and I think that’s a shame. Detroit continues to try and sweep its blunders under the rug instead of owning up to them and trying to make them right.

If it’s demolished, at least we’ll see what they hid in the cornerstone time capsule, right?

Update - March 18, 2024

Sometimes, demolitions have silver linings. A few weeks ago, I got a message about this article. They asked about the time capsule that was reported to have been buried there when the cornerstone was laid. I didn’t have much information, but I shared what I knew.

This morning, I got a message that the time capsule had been salvaged and was headed to the city for placement at the Historical Society!

The person who messaged me said, “It was literally inside the cornerstone. We had to break it open to get it out. If it wasn't for your article it would have ended up in the landfill.”

Special thanks to the employees at Homrich who recovered it and turned it over to the city. Sometimes, it pays to be curious!

Update - April 4, 2024

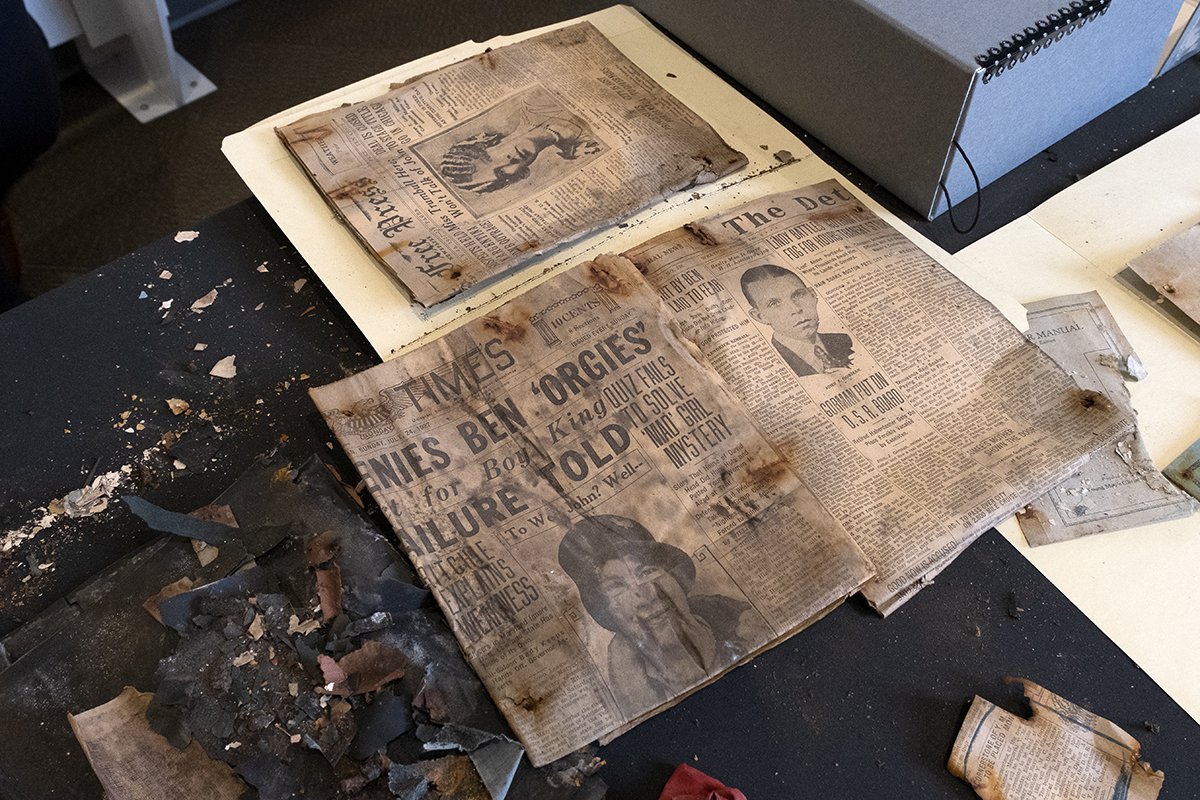

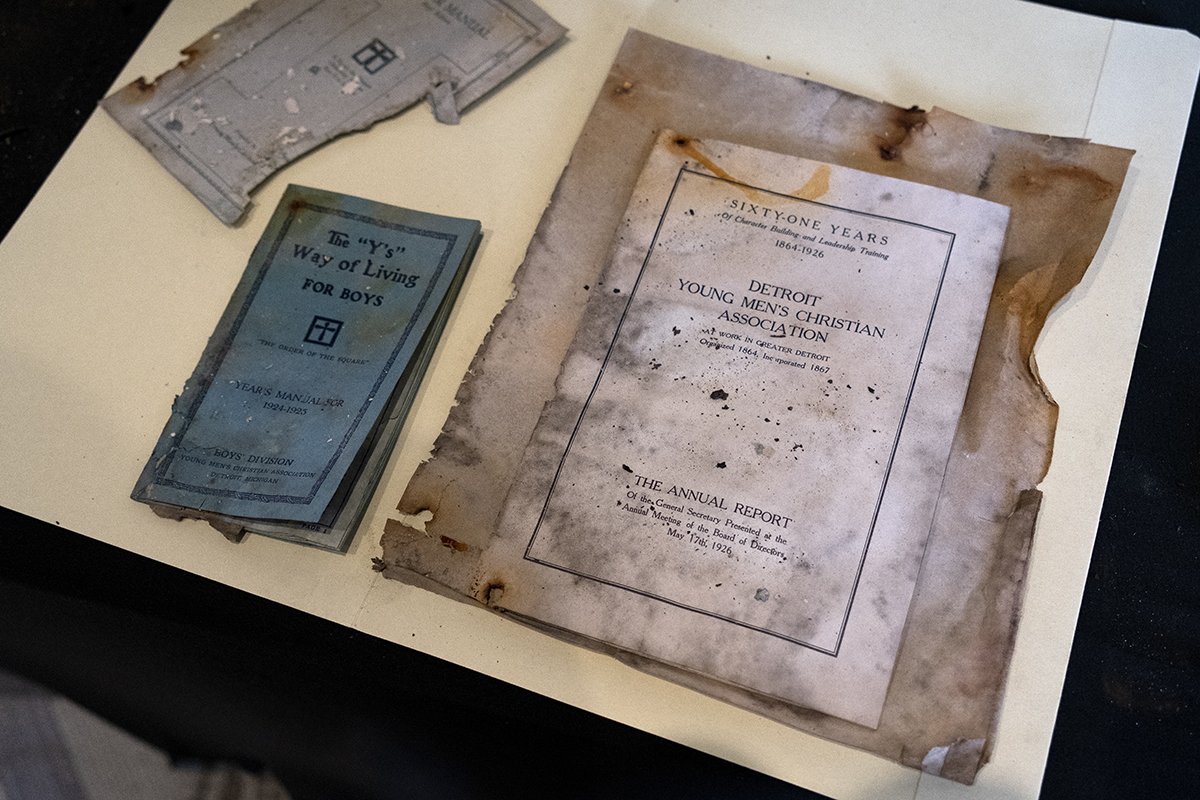

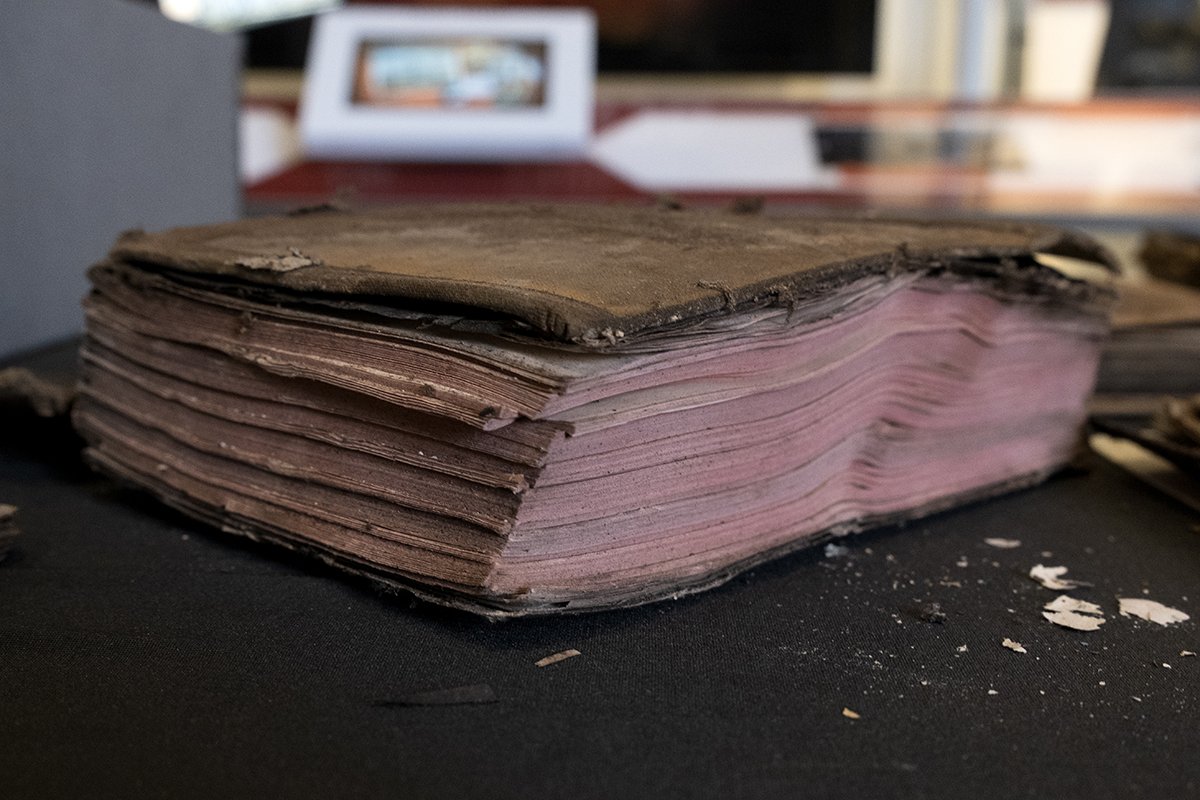

Today, I was invited to the Detroit Historical Society, as they were set to receive the time capsule salvaged from the cornerstone of the Hannan Memorial YMCA at 10401 East Jefferson Avenue. Unfortunately, I had to work, but I was able to stop by near the end and see what was inside.

Thanks to the precise work of Jeremy Dimick, the Director of Collections and Curatorial at DHS, much of the contents were saved from the cornerstone, which was put in place during a ceremony on July 25, 1927. Surprisingly, some of the contents were in sound shape, at least for nearly a century-old items.

The next step is to take the items to the Detroit Historical Society’s warehouse to be dried and cleaned. There’s a chance that some of the materials will be scanned and uploaded to their online archive at some point, but that will depend on the condition and relevance, I’m sure.

Regardless, I’m incredibly joyous that crews from Homrich went in to retrieve it, and the DHS has taken such care to preserve it.