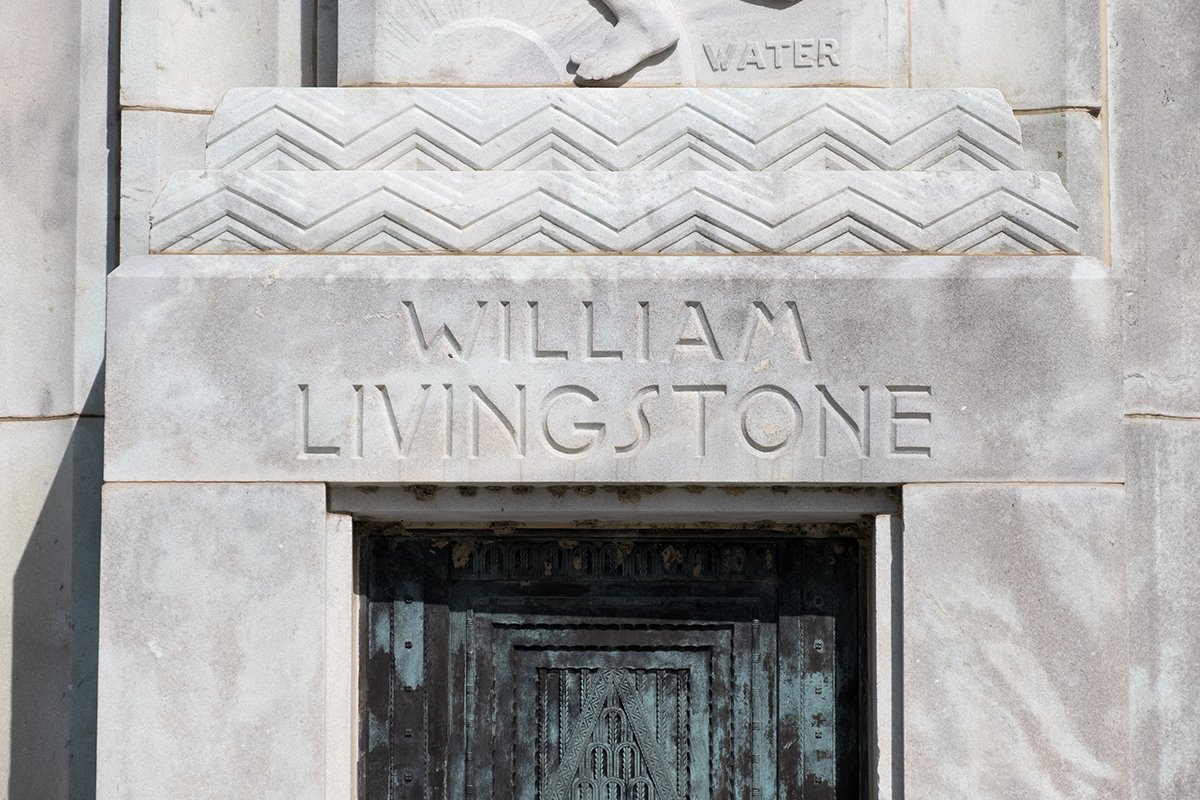

William Livingstone Memorial Lighthouse

Belle Isle, Detroit, Michigan

I’ve spent more time on the far side of Belle Isle than anywhere else on the island. That said, until recently, I didn’t know much about its history. This is an article about the William Livingstone Memorial Lighthouse; however, it’ll cover a more general history of that part of Belle Isle from the 1880s until today.

In September 1881, work on the first Belle Isle lighthouse was underway. Industrial America was on the rise, and with it came more ships on the Detroit River, moving everything from European textiles to Keweenaw copper. Belle Isle was a much more rugged place back then, so light was necessary to keep ships from running aground on its swampy shores.

By October. William E. Avery of Detroit had been given the stone contract for the lighthouse. That entire end of the island was a swampy mess, so land had to be filled in to construct the light. At a total cost of $16,000, the light was illuminated for the first time on April 13, 1882, with Anson Badger working as the first keeper.

Perhaps the most famous keeper of the Belle Isle Lighthouse started in 1886. Louis Fetes loved his job, as he was far from the growing city across the Detroit River. There wasn’t a bridge to the island until 1889, but the island wouldn’t see significant developments for a few more years. When Fetes started, to get back to Detroit for supplies, he’d row a small boat to Canada, walk a few miles to Walkerville, and take the ferry to Detroit.

The lighthouse was next to a large marsh, where Fetes would fish for perch. When the canals were built on Belle Isle, they filled in more of the marshes, and the island’s landscape continued to change as roads were built around it. Of all the people tied to Belle Isle’s history, Fetes likely saw the most change on the island firsthand, watching it transition from rugged wilderness brimming with wildlife into a developed place for Detroiters to unwind. He’d retire after 42 years, calling it quits a few years before the structure pictured here was dedicated.

On October 17, 1925, William Livingstone died. He was a sailor, banker, publisher, and clubman. More specifically, he was president of the Lake Carriers’ Association for more than 25 years, president of the Dime Savings Bank, where he died in his office downtown, and a friend of Henry Ford. Those close to Livingstone wanted to build a testament to a man who meant a lot to Detroit and the shipping industry in the Great Lakes Region, so it was proposed that a lighthouse be built on the far end of Belle Isle to honor him.

The lighthouse was set to work in tandem with the old lighthouse, not replace it. According to the Detroit Free Press, the model shown to donors “was designed and built by Professor Geza R. Maroti,” and Detroit architect Albert Kahn was set to supervise the construction. The federal government approved the plan, and the United States Department of Commerce, which controlled lighthouses in the U.S. until 1939, was set to maintain it.

On October 17, 1930, dedication services were held for the William Livingstone Memorial Lighthouse. George A. Marr, the vice president of the Lake Carriers’ Association, spoke at the event. Standing 58 feet tall, consisting of Georgia Marble, and costing $100,000, the lighthouse was one of a kind. More than 500 of the who’s who of Detroit were in attendance, and Charles Beecher Warren presented it to the city from the donors. Frank Murphy, then Mayor of the City of Detroit, accepted it on the Motor City’s behalf. The date marked the fifth anniversary of Livingstone’s death. From images and maps, the lighthouse may have been closer to the water when it was constructed.

Technically, this lighthouse is the second to bear Livingstone’s name. As an advocate for Great Lakes shipping, Livingstone was integral in widening and deepening the channel between Lake Erie and the Detroit River, which reopened in 1912 after 9.5 million cubic yards of material were removed from the water. The channel, named after Livingstone, was home to the Livingstone Channel Lighthouse, which was completed in 1915 and is technically in Canada. In 1952, it was struck by a ship in dense fog, causing it to lean dramatically. It was destroyed in 1953 and was replaced by a modern tower, which is still there today. Though not named in his honor, it’s named after a channel that was.

In the Autumn of 1941, the old Belle Isle Lighthouse was demolished. A state-of-the-art Coast Guard Station was built in its place and is still in use today. I’m not certain if it has been updated or not. An article in the Detroit Free Press said “Like so many other Detroit landmarks that already have fallen, it is yielding to progress and modernization.”

In July 1944, Camp Pulford was established on Belle Isle for field training for the 31st Infantry, Michigan State Troops. The camp was named after Lt. Col. Reginald R. Pulford, the late Executive Officer of State Troops. Until late that fall, Companies A, B, and C trained at the camp and barracked in tents in front of William Livingstone Memorial Lighthouse.

In 1944, the Detroit Free Press laid out booming post-war plans for this part of Belle Isle should the Allied Powers be victorious. These additions would include a lakeside chateau, a museum dedicated to fish and birds, and a children’s bathhouse. I’m unsure if any of these plans ever moved out of the research phase.

In the 1950s, the United States built dozens of Nike missile batteries in and around cities that were significant targets due to high population density, manufacturing might, or military bases nearby. Detroit had several bases, and in 1954, the U.S. Army leased land from Detroit adjacent to the lighthouse to construct one, later called D-26. According to military documents, the base had Nike 2B, 2C/12H, 20A/12L-UA, and 8L-H missiles. Roughly located between the Blue Heron Lagoon, William Livingstone Memorial Lighthouse, Detroit River, and Lakeside Drive, the base’s double launch area could defend the Detroit-Cleveland area from Soviet attacks. Luckily, these missiles were never used, and the program was scrapped entirely by 1974.

When the U.S. Army leased the land in 1954, military officials agreed to restore it to its original state if and when they closed the base. However, after terminating and abandoning the base on September 15, 1969, a Civilian Army Engineer told city officials that the federal government assumed no responsibility for cleaning up their mess. Luckily, lots of negative press made them change their minds. The city wanted the “top three feet of concrete removed from the underground missile silos” and told the Army to “break up the remaining concrete to allow underground water to percolate through the silos.” The silos were filled with concrete and dirt, roads on the site were destroyed, the makeshift dump was cleaned up, and the entire area was covered with sod. City officials planned a picnic area on the site. Likely, underground, there are still remnants of the missile silos.

On August 19, 1980, vandals broke into the William Livingstone Memorial Lighthouse and stole two of the four panels that operated the light atop the tower. Handcrafted in Paris around 1850, they were not replaceable. Additionally, the thieves stole a brass shield and other fixtures from the light. At the time, brass’ value was high, so that’s what Detroit Police assumed was what they were after. The vandals broke windows at the top of the lighthouse and spray painted graffiti inside. At the time, the lighthouse was protected by a smaller, wrought iron fence, which I believe is the same one that’s still there today. After the theft, a larger gate was installed that blocked off an entire portion of the island.

In 1991, the lighthouse underwent renovations. I’m not certain what work was completed, but the lighthouse has been, for the most part, well-maintained over the years.

In 1992, a proposal was set to completely change that side of Belle Isle. Developers wanted to build an equestrian facility around the lighthouse and on the land formerly occupied by the military base. Made in Detroit, Inc., wanted to build horse corrals, a multi-purpose field, an amphitheater that seated 10,000 people, a riding area and stables, a parking lot, a restaurant, and a hunt club. Later plans from the corporation, led by William Merriweather, added 400 boat slips on the Blue Heron Lagoon, a health club, a banquet center with meeting rooms, fast food restaurants, and retail shopping.

Many members of Detroit’s City Council supported it, and it had the blessings of Dennis Archer, Detroit’s Mayor, too; however, he thought that the boat slip idea was stupid considering how many vacant marinas the city already was maintaining. The Friends of Belle Isle opposed the proposal, and many Detroiters agreed it could disrupt the island’s nature and recreational opportunities. The plans never materialized, and this part of the island remained relatively undeveloped.

In 1996, the same group attempted to get a development off the ground on the water in the Trenton/Gibraltar area. The plan for homes, a golf course, stores, and restaurants failed because it was on top of a coastal marsh and river system.

Back on Belle Isle, not much happened at the Livingstone Memorial Lighthouse in the 1990s and 2000s. In 2013, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources took over the island, and things started to change pretty quickly. Still, this area remained relatively quiet. You had to pass the lighthouse to get to Hippy Beach, a mystical bit of sand and water on one of Belle Isle’s Canals. In 2018, somebody tagged the lighthouse with graffiti, which took ages to be cleaned up.

As Detroit increased in popularity, this area quickly became a common place to find hikers, people fishing, and the occasional nudist. Eventually, Hippy Beach’s famous rope swing was dismantled by the DNR, and more developed walking paths were established. When Lake Okonoka was dredged a few years ago, all of the raw materials were thrown into the area where the former military base was, which stunk for a while but has turned into a grassy area.

Depending on which way you’re going, Michigan’s Iron Belle Trail starts or ends here. Connecting Belle Isle in Detroit to Ironwood in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula with two trails, one for hiking and one for cycling, an art piece and plaque were installed here to commemorate the trail in 2022. The parking lot was also upgraded, with a paved parking area and more spaces for when things get crowded in the summer.

The William Livingstone Memorial Lighthouse is still operational today, though it’s not as instrumental in navigating the river as the original Belle Isle Lighthouse once was. In working on a boat on the Detroit River for a few years, I never heard anyone call out over the radio to look for the Livingstone Lighthouse. Still, it’s an incredible piece of history that ties some of Detroit’s most influential figures to the city’s most famous park.

Belle Isle is a safe haven and one of my favorite places in the entire city, even in the Winter. When hiking by the lighthouse, it’s hard to imagine everything that happened there. This space has seen everything from a meeting of 500 of Detroit’s most influential people in 1930 to military barracks during World War Two, a U.S. Army missile base during the Cold War, and nearly becoming a horse park in the 1990s. Who knows what the next century might bring?